Jun 23, 2023

The 23rd of December 1947 is a day I’ll never forget. That is when I first learned, to my horror, what a circumcision was.

I was raised Roman Catholic and attended 12 years of parochial school. That day marked the last class before Christmas break, and the teacher (a nun) explained why January 1 was a holy day of obligation. (It’s the Feast of the Circumcision.)

In that moment, I understood immediately what had been done to my body. I understood why I was never comfortable there and why my clothes were always irritating me. I realized then that the head of my penis was meant to be covered. It was this unnatural exposure that was causing me to experience an almost constant state of semi-arousal. It’s not normal to be exposed that way. Being sexually aware and acting on that awareness are two, very different, things. I was an introvert, and thus a shy child, and there was no one with whom I could speak. I never broached the subject with my parents because I knew they would dismiss it, hoping I’d forget about it.

This is not considered a “normal” preoccupation, but then, having a scar encircling one’s penis isn’t “normal” either in most of the world, no matter how much our American culture insists that it is.

As a gay man who had wished since childhood for a foreskin to soothe the constant discomfort, I always found the circumcised penis ugly and to be a turn-off. It’s difficult to explain the trauma of being unable to discreetly identify intact gay men with whom to engage in sex, especially as an introvert.

This act that was done to me without my consent makes me very angry. I’ve channeled that anger into researching circumcision and the arguments for and against it for more than 75 years now. I still don’t understand why someone would amputate a normal body part simply because they have accepted without question the notion that it’s not clean.

For some reason in American culture, we don’t talk about the penis in a matter-of-fact way, and we definitely don’t talk about its foreskin—except to say that it’s dirty. What this is referring to is smegma, a word normally heard only in the context of jokes. Smegma is a natural lubricant the body produces to prevent the foreskin lining from adhering to the glans. It’s made of body oils, skin cells and moisture. Every body produces smegma—it’s between our toes and behind our ears, anywhere skin folds against itself. We just give it a quick wash and get on with our day.

The idea that a foreskin is dirty is a uniquely American notion. We’ve been cutting it off for six generations. We’re the only advanced nation where cutting off the foreskin of a male infant is routine practice, and we don’t even know why. The medical community makes all sorts of excuses that don’t hold up to science—while the rest of the advanced nations think we’re crazy. It’s sexual violence on an infant. It’s just insane.

But it’s so normalized. At a recent medical appointment, the doctor asked me to list every surgery I had ever had. I included circumcision on that list, but when I reviewed notes from the appointment, I realized she had left that one off. It has become so ubiquitous that she didn’t even mention it.

I’m 82 years old, and I’ve become more outspoken about this. I have repeatedly sent email letters to my congressmen and women and my senators, and their response is, “There, there. Don’t worry about it. We’re taking care of you.” They don’t see the harm that’s been done. I really feel that most American men have the attitude that it was done to them and there’s nothing they can do about it now. But it’s a human rights issue. And no one wants to listen.

— Wallace Muenzenberger

Interested in lending your voice? Send us an email, giving us a brief summary of what you would like to write about, and we will get back to you.

Jun 23, 2023

May is Masturbation Month. If you missed it, you can always indulge belatedly!

Intact America followers probably know that circumcising boys (and even girls) by doctors began around 150 years ago as a “remedy” for masturbation. Victorian era doctors believed that onanism (another term for masturbation) could cause lunacy and many other diseases, both moral and physical.

Journalist David Gollaher, in his book Circumcision: A History of the World’s Most Controversial Surgery, writes about how cereal magnate John Harvey Kellogg “recommended performing circumcision ‘without administering an anesthetic, as the pain attending the operation will have a salutary effect upon the mind, especially if connected with the idea of punishment.” Other doctors in the late 19th century advocated for the use of blistering fluids on the genitals (of boys as well as girls) to both deter and punish self-pleasuring.

Amazing, isn’t it, that this history has been lost on those who deny that circumcision harms boys and men?

If you’re over 50, you probably remember the brouhaha when Surgeon General Joycelyn Elders in 1994 talked publicly about masturbation as a natural and positive human behavior. She was ridiculed and eventually resigned from her post, but not without removing some of the stigma surrounding the subject. A year later, the sex shop Good Vibrations declared May National Masturbation Month. Put it on your calendar, but no need to wait until next year to celebrate!

Dec 4, 2022

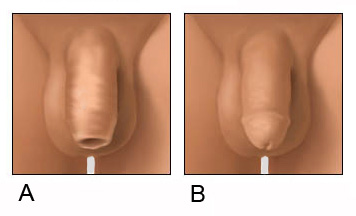

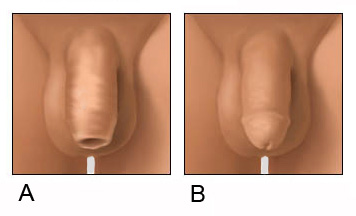

Two recent surveys by Intact America have raised the question by some participants of why we asked the men if their penis looked like A (an intact penis) or B (a circumcised penis), which they found either distasteful or an invasion of privacy. This is the A or B image they were talking about.

The short answer is accuracy. Asking this question improves the quality of the survey results. A lot. The reason is that many men don’t know their penile status! A 2004 study of college-aged men found that 33% were mistaken or unsure of their penile status.[i] This is nothing new, a 1960 study found 14% of men were unsure; their status was confirmed by a physical examination.[ii]

More recently, in Intact America’s three, national random sample surveys (2017, 2018, & 2021) of 3298 Americans, 14% of men were mistaken or unsure of their penile status. See below for my decade-old methodology to determine whether men were mistaken or not. But first, here’s an entertaining anecdote to illustrate the problem.

You may have seen the episode of the Graham Norton Show on BBC in 2017 with guest actor Sir Patrick Stewart. He relayed the funny story about him mentioning in passing to his wife that he was circumcised. According to Stuart, in his 70s at the time, the conversation went something like this:

Stewart: I’m circumcised.

Wife: (laughs) You’re not circumcised.

Stewart: That’s ridiculous! I should know if I’m circumcised! End of conversation.

Stewart: The next day, I happened to be seeing my doctor for my annual physical. When the doc was ‘down there,’ I mentioned my disagreement with my wife, and asked, “I’m circumcised, right?”

Doctor: Not!

Surprisingly, even men who call themselves intactivists, and who are presumably knowledgeable about circumcision and male sexual anatomy, aren’t sure. A survey of intactivists found that 13% of intactivist men are mistaken or unsure.

In 2011, I wanted to learn if newborn circumcision was associated with alexithymia. Alexithymia is the inability to identify and express emotions. It is thought that it is acquired at a very early age. Such people have difficulty in relationships, social interactions, and even in therapy. But I could not examine these men who live across the United States. So, I had to develop a viable validation alternative for that peer-reviewed alexithymia and circumcision study. My solution was to ask their penile status and then compare that with their answer to the A-B image question. Entries that did not match correctly were removed from the dataset.

As it turns out, and unknown to me at the time, I’m not the first researcher to realize that self-report is inaccurate when it comes to penises. In 1992, Schlossberger found that: “Use of visual aids to report circumcision status was more accurate (92%) than self-report (68%).[iii] Wow.

Granted, the best way to determine penile status would be a physical examination. But this is so problematic on so many levels that it would be all but impossible to survey. You’d have to pass certain standards using human subjects, hire medical staff, obtain liability insurance, and of course get permission from the men to disrobe. (By the way, the proper way to determine if a man is circumcised isn’t to look for the lack of a foreskin, but the presence of a circumcision scar.)

The solution that I came up with, and one I’ve used many times since, is a three-part survey-question method. The questioning goes something like this:

Are you circumcised or intact (not circumcised)?

Circumcised

Intact

Don’t know

Which one of these images most looks like your flaccid (not erect) penis?

A

B

Unsure

Are you restoring your foreskin?

Yes

No

I don’t know what this is

As you can see, this method results in much more accurate answers, and provides trustworthy data. Nevertheless, some men are not comfortable answering these questions, even to an anonymous researcher. I can appreciate that. That’s why I’ve taken steps to avoid their discomfort: 1) I inform participants that they’ll be asked personal, sexual questions, 2) tell them they can opt out now, 3) tell them they can opt out at any time, 4) mention that this data will only be used in aggregate form, and that at no time will their identity be revealed, and 5) use the image shown above obtained from a medical illustration stock image source instead of using a photo of real penises.

A study I recently conducted, and now in-press, titled “Adverse Childhood Experiences, Dysfunctional Households, and Circumcision,” also employed this method. None of the journal reviewers mentioned a problem with using this image.

So, not using this tripartite image question would make the results skewed, if not unusable, and therefore unpublishable.

Sadly, many circumcision studies being published since I created this method continue to just ask the men if they are circumcised or not, leaving us unsure of what to make of their conclusions. As scientists like to say: “Junk in, junk out.” (no pun intended!)

—Dan Bollinger

[i] Risser JMH, Risser WL, Eissa MA, Cromwell PF, Barratt MS, Bortot A. Self-assessment of circumcision status by adolescents. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:1095–1097.

[ii] Wynder EL, Licklider, SD. The question of circumcision. Cancer. 1960;13(3):442 5. 14.

[iii] Schlossberger N, Turne R & Irwin C (1992) Early adolescent knowledge and attitudes about circumcision: methods and implications for research. J Adolesc Health 13(4): 293-297.

Jul 11, 2022

Dear Marilyn:

Everything about my son’s birth was great. Except for one thing that keeps bugging me. Even though we knew early on that we’d keep him intact, people kept asking us if we wanted to circumcise him. I told my OB/GYN we didn’t want to, but on the next visit she asked. In the hospital, just about every nurse asked me even though our choice was written on my chart. This happened over and over before and after the birth. I was so angry I wanted to scream. Why do they keep asking? It made me begin to question our decision. Don’t get me wrong, I’m glad we didn’t, but geez, why weren’t they listening?

—Alice, Fort Myers, FL

Dear Alice:

Congratulations for having the strength to protect your son’s right to his own body and withstanding the pressure of those who tried to coerced you to cut off the most sensitive part of his genitals. Circumcision is BIG business—a $2 billion-dollar-a-year industry for an unnecessary and harmful amputation, which is why doctors and nurses “sell” it so hard.

Doctors and nurses won’t admit it, but they know that circumcision is excruciatingly painful and traumatic. That’s why they do their genital cutting behind closed doors and prevent parents from hearing the screams or watching their babies suffer.

By keeping parents in the dark, health professionals can convince vulnerable and exhausted parents, right after their child is born, to circumcise their baby. If more parents knew what circumcision involves, they could stand strong and resist the pressure.

For example, a colleague and I videotaped a circumcision at the hospital where we worked. A childbirth educator showed the circumcision video to her class, and not one of the mothers circumcised their sons as a result. The educator showed it again to a second class of mothers. They didn’t circumcise their babies either—except for one doctor who was taking the class. Even worse, the doctor insisted that our video be censored. That’s how much doctors dread letting the truth slip out.

Fortunately, several anti-circumcision movies are available now that include actual circumcisions. I suggest watching The Circumcision Movie. Not only will you see that you and your husband were correct to protect your son, you’ll also learn that you are not alone in denouncing this anachronistic blood ritual.

—Marilyn

Oct 2, 2021

One rationale people give for male newborn genital cutting (aka circumcision) is “do it, he won’t remember it.” This is a bogus claim. First, it presumes circumcision is a better-do-it-now-rather-than-later birth imperative. The second rationale, a fallacy which follows closely on the first, is that the boy’s still-developing brain is incapable of creating long-term memories. But this is not entirely true. Research has shown that the more traumatic an early experience is, the more likely it will be remembered.

Over the years I’ve had a lot of conversations with men about circumcision. Out of curiosity—and because of my own night terrors I associate with my own newborn circumcision—I asked them if they have an early recollection that they think may be related to their newborn circumcision. What surprised me was that about one out of five said yes.

In 2010, I surveyed men to determine if experiencing newborn circumcision, could lead to acquiring alexithymia, the inability to identify and express emotions. It does. Out of curiosity, I asked them if they have an early recollection, a “snapshot,” or night terror that they associate with their circumcision. Of the men in the study who were cut as newborns, 20.3 percent answered yes or maybe. Recently, I conducted a survey regarding Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and 23.4 percent of the men also answered yes or maybe to the same question.

Granted, it is impossible to verify if an early memory is true. But before you pooh-pooh these early memories, consider that the large and consistent percentages across these surveys strongly suggest that they are true. Regardless, listening and acknowledging these stories should be part of the circumcision debate.

By Dan Bollinger