Is Circumcision in America Really “Deeply Religious”?

Things have changed considerably in just the last few years with respect to mass media and the topic of circumcision. Several articles are published every month now – if not every week — in major newspapers and websites here in the U.S. and abroad.

As a result, it’s somewhat of a luxury to find myself being critical of a piece written by an author who self-identifies as a “Humanist” and presents his personal views as “progressive” on the topic of circumcision.

As a result, it’s somewhat of a luxury to find myself being critical of a piece written by an author who self-identifies as a “Humanist” and presents his personal views as “progressive” on the topic of circumcision.

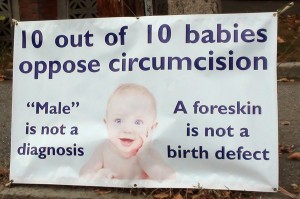

In his report on a recent intactivist street protest where he interviewed several of the demonstrators, he states, “… my own feeling is that we should not be surgically altering the genitalia of our children without their consent, and that consent can only be given when the child is of legal age.”

What more could you ask, right?

But in an attempt to identify the root cause of the inertia that stands in the way of the real progress made to end circumcision in this country, the author relies on an unsubstantiated claim that conflates notions of American progressivism with unwavering support for religious freedom.

He says, “Circumcision has a deep cultural and religious meaning, and asking people to give up on that practice will be a long, uphill battle.”

The truth is that in the United States, only a tiny fraction of infant circumcisions are conducted as religious rituals. Jews constitute just two percent of the U.S. population. Of those, only a few say religion is very important in their lives.

While no study I’m aware of has been done to uncover current attitudes and thinking specifically about circumcision among American Jews, it’s clear from the number of Jewish intactivists, from the Jewish physicians I know who have refused to have their own sons circumcised, and from information gleaned over the years I’ve been involved with this issue, that many, many Jews forgo the bris, which is the only way of achieving a religiously valid circumcision. And, it’s well known among health professionals that American Muslims have their sons circumcised by the doctor, before they leave the hospital, rather than as part of any religious or “spiritual” ritual.

The author also ignores the much more interesting and inherent conflict between a commitment to human rights and a knee-jerk “progressive” reluctance to condemn a religious practice that violates those rights – all of this while buying into the fallacy that circumcision’s “deep cultural and religious meaning” is the major roadblock to ending its practice in the U.S.

Except for misplaced anxiety about whether siding with the rights of the child will brand one an anti-Semite, circumcision in America has almost nothing to do with religion. Yet doctors and hospitals exploit this myth in order to sell an unjustifiable but money-making surgery.

Georganne Chapin